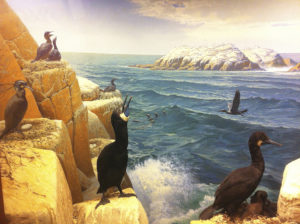

Here are nine of the fifteen or so dioramas that Fred Scherer painted at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. In his early years as an assistant to his mentors, James Perry Wilson and Francis Lee Jaques, Fred also worked on numerous other back-grounds such as the American Bison in the Hall of North American Mammals. In an entryway corner at the back of this hall is a plaque that gives all the artists’ names and a short video about the dioramas.

Fred F. Scherer (1915-2013) By Sean Murtha

Visitors to the famed diorama halls of the American Museum of Natural History may not realize that behind the detailed foreground models and impressive taxidermic mounts can be seen one of New York City’s finest collections of landscape paintings. So well integrated with the foreground and the lighting effects, the casual viewer may not recognize them as such, but careful inspection reveals not only a rich painted surface, but also the stylistic touches of a variety of different artists.

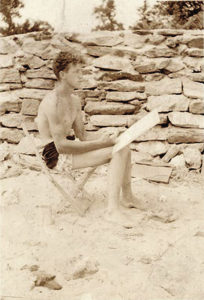

Until his death at the age of 98, Fred Scherer (1915-2013) was the last remaining artist from that generation who created dioramas at the AMNH in its “golden age” from the 1920’s to the 1940’s. In his 38-year career at the museum, he painted over 15 diorama backgrounds and assisted in many more. The museum was also his primary art education, where he was trained and mentored by the pioneering artists of the genre. Dioramas were at that time a cutting-edge exhibition technique, and great lengths were taken to maintain accuracy and realism, including sending the artists into the field to paint studies from the actual location, a practice that Scherer remained devoted to long after his retirement from the museum.

Born on March 1, 1915 in Ozone Park, Queens, NY, many of Fred’s eight siblings were interested in art, perhaps inspired by their printer father. Fred did not remember having art instruction in school, but he remembered copying Popeye the Sailor and other characters from the funny papers. At some point his older brother, William, began taking Fred out to Long Island to paint landscapes, beginning a life-long practice of painting outdoors. This method is often referred to as “plein-air” painting, though to him it was simply a natural way to approach landscape, requiring no descriptive label. Fred won a Guggenheim prize for artwork in high school.

It was not painting, but a clay sculpture of a Polar Bear that got him his job at the AMNH at the age of 19. After a year working under a special WPA apprentice program, he was hired permanently in 1935. This was an ambitious period of diorama creation at the Museum, and Scherer was introduced to background artists such as William R. Leigh, Francis Lee Jaques, Belmore Brown, and Carl Rungius

But it was James Perry Wilson (1889-1976) who would have the greatest influence on the young Scherer.As his painting assistant, Scherer received an unparalleled art education. Wilson was an avid plein-air painter, possessing a rare expertise in a variety of fields that informed his paintings with an uncanny fastidiousness and fidelity to the real effects of light and atmosphere. Solitary by nature, Wilson found in Scherer a willing pupil and shared his knowledge generously. Fred remembered many lunch-hour walks in Central Park with “Perry” (as Wilson was known to his friends) looking at and discussing “…bridges, stonework, natural stone, light that would do this and that, the weight of things…” Fred continued to see the world through Wilson’s analytical and artistic eyes and to pass on his knowledge in the same way. Several years ago, for example, while driving with Fred to a restaurant, he was so absorbed with observing and describing the colors of the roadway as it crested a hill, and the effects of distance on the colors of the trees, that we continued several exits beyond our destination!

From Michael Anderson’s Painting Actuality: Diorama Art of James Perry Wilson:

“Fred Scherer, diorama painter and colleague at the American Museum of Natural History recalls that Wilson said he spent more time watching the action of the waves than painting them. Fred Scherer, who painted under Wilson’s tutelage at the AMNH, recounted how Wilson painted backlit leaves to get a “stained glass” effect. Scherer knew Wilson as a religious man and that this type of effect translated into spiritual terms. He went further to note, “He put his heart into the landscape. It’s almost spiritual in a way. You can sense it and see it. When he looked out over the landscape, I’m sure he felt it”

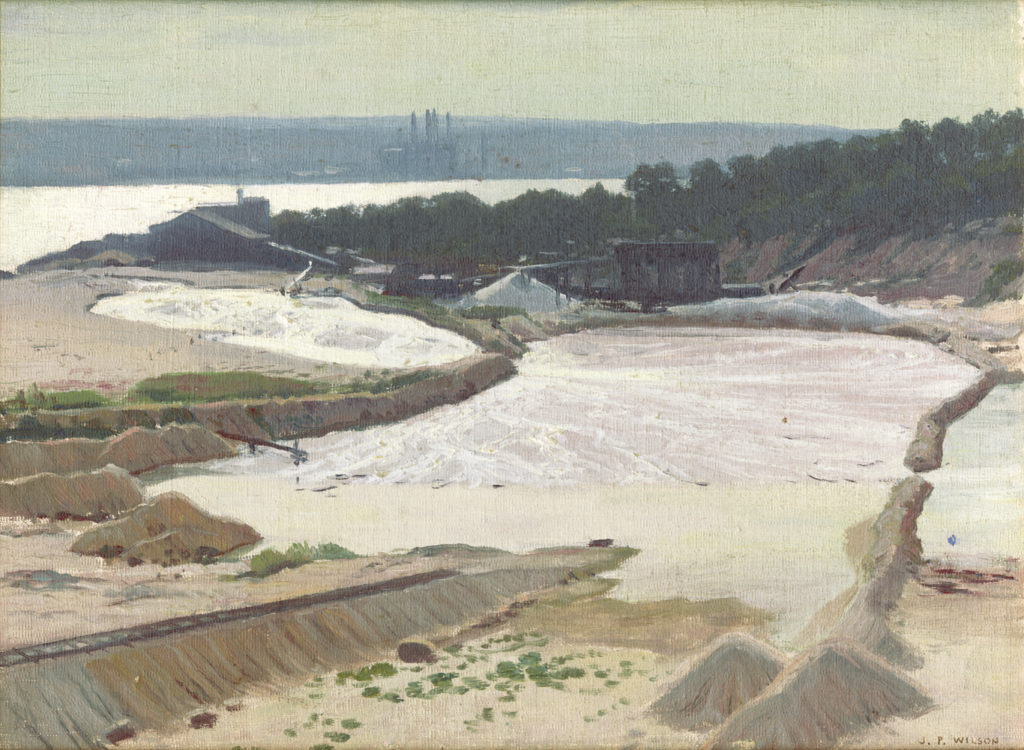

Scherer and Wilson often painted together on weekends, taking their easels to New York City locations. Fred treasured a 12” x 16” canvas panel by Wilson of a sand quarry in Hempstead, Long Island, the result of a day spent painting together which ended in a trade of the finished paintings. “I got the better end of the deal,” said Scherer with humility, but Wilson obviously admired Fred’s painting, which unfortunately remains un-located.

Meanwhile, Scherer’s talent was eventually recognized at the AMNH to the point where he was given entire backgrounds to complete independently. His earliest backgrounds were based on studies done by other artists, but in time Fred was sent into the field to obtain his own plein-air studies. A particularly memorable trip was to Churchill, Canada, location of the Tundra Diorama. While painting in this isolated, barren, windswept wilderness, he became aware of a feeling that he was not alone. Turning around, he saw a pack of feral dogs stalking him. They were hunters’ sled dogs, left to fend for themselves for the summer like wild animals. Fred was unaccompanied and unprotected, but his instincts were good; he slowly sank into a squat, and then suddenly leapt upwards with a yell, swinging his palette and brushes overhead. The dogs scattered, and Fred resumed painting.

Despite Wilson’s deep influence, Scherer’s work is no imitation of his mentor. From his earliest dioramas, Scherer cultivated his singular, assured touch -a looser hand than Wilson’s -with a taste for experimentation and expressive brushwork. His dioramas are perhaps best recognized by his use of “pointillism” or “broken color,” and this stylistic approach has informed much of his later work. When asked how he first began using the technique, he shrugged vaguely; “I might have seen some old paintings,” and admits that he had some trouble getting it by his superiors. On a visit to his studio I noted a thick book about Seurat, but Scherer’s work is quite different than the French pointillist. Where Seurat’s paintings dissolve form, Fred’s use of juxtaposed points of color actually enhanced it, and he was able to retain a full range of values.

When Scherer retired from the museum in 1972, he and his wife, painter Cicely Aikman, moved to Friendship, Maine, where they resided until moving to Vermont in 2007. Those years in Friendship were perhaps his most productive, especially in plein-air work. Their home, situated on a diverse parcel of trees and garden, sloped down to a panoramic view of quintessential Maine shoreline, where Fred had built a summer studio for Cicely. Many of his paintings from this time were done on this specific property or in the immediate area. A frequent motif in his Friendship paintings was an erratic boulder perched on a low peninsula of rock, which was a prominent landmark in the cove below the studio. An expressive oak in his front yard was another frequent subject, painted in all seasons, in sunlight and in moonlight, as well as nearby orchards, sheds, and barns.

Scherer’s outdoor paintings were characterized by an assurance developed through a lifetime of working from nature, though he never ceased to experiment with method and medium. His colors are vibrant and his shapes bold; his brushwork is loose and never fussy, with little blending. In this, his mastery of “broken color” reveals itself; subtle juxtapositions of color vibrate against each other, describing form and texture with only a suggestion of detail. One of Fred’s greatest gifts was his ability to make artistic sense out of the non-descript chaos of, say, a brambly hedge, finding just the right colors and rhythms to make it interesting. Elsewhere he chose to describe an area with one broadly painted tone; these surprising decisions and variety of handling kept Scherer’s paintings constantly fresh and exciting. Underlying this use of color and texture is the ever-present sense of right-ness, the careful nuances of atmosphere and value relationships that hold his paintings together in a way that betrays his training as a diorama painter—a training that emphasized reliance on observation and experience over mere bravura realism or romanticism.

Scherer’s diorama work has been seen by millions at the AMNH, though few are aware of the artists’ names. He also has painted murals at the State Museum in Augusta, Maine, and has another in the collection of the Blauvelt Museum in Oradell, NJ. Since the 1970’s, Scherer has exhibited in Vermont at the Gallery North Star in Grafton, and the Crowell Gallery in Newfane, on the Maine Coast in Rockland at the Caldbeck Gallery, the Harbor Square Gallery, the Farnsworth Museum, and the Maine Coast Artists as well as in Damariscotta, Waldoboro, Wiscasset, and at the Portland Museum of Art. He has exhibited with his wife, Cicely Aikman, oil painter, and his daughter, Deidre Scherer, a renowned fabric artist.

Fred was a devout man, intensely spiritual, and perceived the hand of God in the beauty and variety of nature. A walk in the garden with Fred revealed that to him, there is no separation between scientific observation, artistic expression, and worship of the divine. Occasionally, he had experimented with paintings with personally spiritual content, such as an unusual “self portrait” of his own shadow (and that of his cat) against the wall of his house. Done in his mature pointillist style, the entire painting is a rich tapestry of colors, but the shadow is truly radiant; an explosion of color like Van Gogh’s night sky that describes not the absence of light but the presence of spirit.

Even in his less overtly spiritual paintings, however, there is always a vibrancy in the light and a meditative calm that evokes a sense of something beyond. Despite a lifetime of careful study of the world around him, Fred was always transfixed and humbled by it, and experienced it with the wonder of a young boy making his first discoveries. Looking out of his window during one visit, he reflected on the overlapping boughs of trees at the forest edge, emerging from the deep shade into the soft light of a cloudy-bright day. His thoughts and words merged in a way that was more poetic than conversational. “Trees that are in the light, the darkness gets in around it… it’s beautiful, and a painter that can get that feeling into it, is successful.”

Many thanks to Mike Anderson, Joyce Cloughly, Steve Quinn, Paul Breslin, Jan Ellen Scherer-Dufner, Deidre Scherer, and the AMNH Library for permission to use images from their collections. Special thanks to Sean Murtha for his blog article from 11/26/2013.